This past week, my company held its annual performance evaluations. Our company has a pretty simple process – a short form completed by both the employee and the supervisor, then discussed in a one-hour meeting. The evaluations were partly about past performance, but largely dealt with our goals for the coming year and any obstacles to our performance. Our corporate culture revolves around weekly and monthly meetings that are focused on our tasks, so someone who was outright failing to live up to his obligations would know well before the annual evaluation. I found these evaluations to be a good time to talk about bigger picture issues, including longer term career goals.

I’ve been in organizations with more formal evaluations and some with much less or nonexistent evaluations, with both longer and shorter leashes. When I was delivering pizzas, your “performance evaluation” happened every single night. Poor performing drivers were weeded out quickly; if your work took a sharp dip south (as happened to one driver I knew), it didn’t matter what your annual record might be – you’d be on your way out.

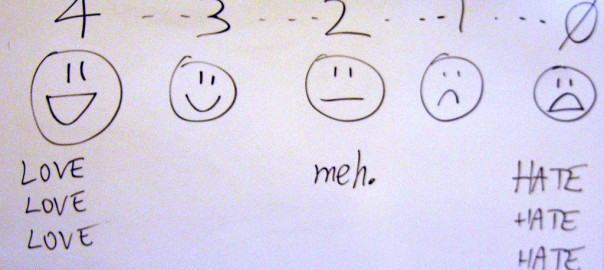

In most corporate environments, though, my performance evalutions have revolved around annual goals tied to my job description. They’ve usually include a rubric of corporate values or performance measurements – teamwork, leadership, effectiveness – with some sort of scoring scale. Usually, these goals have related directly to my daily work, except in one unfortunate case when not only did my annual goals have very little to do with my actual work, but they were changed every few months by my supervisor, making it impossible to know whether I was really performing up to expectations.

Celebrating Achievements, Receiving Feedback

I find performance evaluations to be incredibly stressful. At the end of a typical day, I’m much more likely to worry about all that I haven’t gotten done than to celebrate the things that I have gotten done. When I started my current job, my wife bought me an accomplishments journal that I could use to keep track of what I’ve done. I don’t update as much as I’d like – due to forgetfulness and neglect, rather than a lack of activity – but I can use my daily journal as a reminder of how I’ve spent my time.

If someone has made it to their annual performance evaluation, they ought to have a sizable number of accomplishments to celebrate.[1] The annual review, then, should be an opportunity celebrate together, employee and supervisor, the progress that has been made over the past year. It ought also to be an opportunity to receive honest feedback about areas that need improvement or ways that the employee can take the next step forward in their career.

Compared to What?

One of the problems with performance evaluations is that the standard for comparison is often unclear. Even when companies have a long list of success factors or employee expectations, these are often subjective in nature, relying too much on supervisors’ perception of the employee rather than on objective measurements. Simply being seen at work has an outsized effect on managers’ opinions of employees, especially when there aren’t clear, objective measures of performance.

Other times, though, objective measures can reduce employees to mere numbers. A recent Radiolab story on Internet delivery services described the brutally efficient logistics systems behind Internet shopping. In those industries where workers are constantly measured against exacting performance standards, there need to be humanizing elements to resist reducing employees to the level of drones.

Realistic Expectations

Then there’s the danger of unrealistic standards. Recently, I held a meeting with my team to plan our work for the upcoming month. Before the meeting, I totalled up the number of hours available to us over the next few weeks. In the meeting, we broke down our high-priority projects into distinct tasks, small enough so that we could create somewhat accurate estimates of the time needed to complete them. We quickly realized that not all of our “high-priority” projects could be done in the time we had available, and we were forced to reduce the number of projects planned for the coming month. By the end of the meeting, though, we had a clearly defined list of everything we planned to do.

Afterwards, one of my team members told me that this planning was extremely helpful to him. Before, he had just seen a huge list of projects, all of which had to be done NOW, and he had no idea when he would havet he time to get to them all. Once we had finished our planning, though, his list was no longer huge and indefinite: while it was still long, there was a definite end to it, and it was doable within several weeks. It was now safe to ignore all the other projects on his list, because we had decided not to do those this month.

Imagine, though, if we hadn’t held this planning meeting, and he had been held accountable for the full, impossible-to-complete list. He might have done amazing work over the course of that month, but he would have seen the huge list of projects – due NOW – and felt dismay rather than a sense of accomplishment.

So, to evaluate our performance, we have to know the standards by which we are being judged. Only when those are clear can we be evaluated fairly.

That’s not all, however. For effective evaluations, there must be a sense of trust and confience. More on that in my next post.

Photo credit: Bill Sodeman via Flickr

- If they don’t, or if they have been failing to live up to their expectations, I hope they’ve received warning long before their annual review! ↩